Is there closure in life, ever? Never.

Next year, next day, or next hour presents opportunity for newness. Dynamic processes (more than diamonds) are forever. In loss and in victory, each, best not to rest in the status quo. The dialectic goes on, considered with commitment along Wole Soyinka’s inspiring, anti-quietist lines, “I possess neither the wish nor temperament to abandon the continuing, combative imperatives of the dialectics of human history,” as well as with horror in confrontation with how Nazi-sympathizer/Holocaust-denier David Irving concludes his hagiography of Joseph Goebbels, “There was one feature about the little Doctor, even in death, that caught the Soviet pathologist’s attention. His fists were raised, as though spoiling for a fight. Perhaps, somewhere, for Dr. Joseph Goebbels the dialectical battle was already beginning anew.”1 Need a break? Go ahead, but know that while you rest hostile forces stir.

Onwards, in other words, in mind of Heraclitus recurrently, Strife as the driver of the world, itself an “Ever-living Fire.”

What opposes unites, and the finest attunement stems from things bearing in the opposite direction, and all things come about by Strife.

In between irreconcilables, unanticipated openings arise.

Before the election, before we knew what was going to happen, underneath hopes and fears — a rumbling. The future impended (a paradox of End Times’ boding). In a free and fair election, the worst occurred with regard to voting in authoritarian, oligarchic menace to U.S. democracy. Now the consequences are upon us.

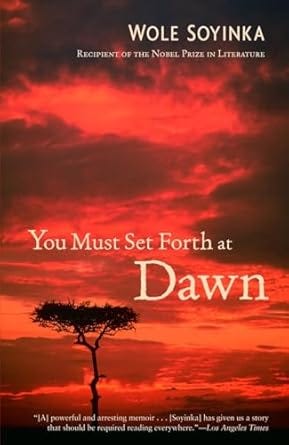

In this abovelinked “Timelessness and End Times” end-of-summer entry, I mentioned Wole Soyinka’s memoir, You Must Set Forth at Dawn, and presented the claim that “Art Singularly Frees” as a gleaning from his cumulative, humanistic — poetic — and staunch response to tyranny, brutal times in his homeland of Nigeria.

also as typo-gleaning then on this website's editing interface: ultimage insightReaction and response balance the cataclysmic. Art, meanwhile — in order to free, singularly — attains to response as distinct from reaction, always. Difficult, recurrent work.

An entry from more than three months ago calibrates after the fact (accessible as it is now to the present) with one from a little more than three years ago, two past spaces in time brought forth in juxtaposition, resonant with an ever unforgivable breach: what a chasm between the responsible and the reactionary!

I took on then the one year anniversary of an outrage and, three years later, this year, nothing — no objections to a free and fair election when the perpetrator wins. The Big Lie is purely functional, believed in only insofar as it serves.

imperfect silence of choking, seething, eels in the throat January 6th irreconcilability — intimate, personal interweaving with the unexpiated historic — birthdate of my father, estranged through death and beyond

Trump indeed got away with it all. The institutions are still intact for the most part, but the humans who had power to do something always passed the buck. Whether for partisan reasons (Mitch McConnell vocally left it up to the criminal justice system to hold Trump accountable after the Senate acquitted him in his impeachment trial for inciting insurrection) or due to a misplaced, timid emphasis on appearances of propriety over urgency (Merrick Garland at the DOJ), key figures failed to stop a traitor. The Biden administration is to blame as well, if only in hindsight: where was the commitment and political daring to bring Trump to justice in time?

Propriety and appearances of propriety are two different things; how about a dash of audacity in staunch defense of the rule of law? — it was too late once a corrupt SCOTUS undermined the basic American principle that no one was above the law (and this after it proved its contempt for women’s rights and health, for basic human rights, with the Dobbs decision).

Today Trump is inaugurated for a second term, with absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts as president. As president, unfit as he is, this guy is as above the law as a king.

“Never give in, never give in, never, never, never — in nothing, great or small, large or petty — never give in except to convictions of honor and good sense.”

Winston Churchill

January 6th failed as an insurrection, but the intent was there, and over these past four years its Big Lie propelled the 2024 election’s outcome, in which the “authenticity” of shamelessness usurped too-modest facts.

Autocratic intent has been handed the means for enactment, with no surprises in its opportunistic gathering of oligarchy and a lackey cabinet. Incoming corruption and degradation of institutions are to be expected. Now, suddenly, something added, something new; ravings as always, cackling, yet in the weeks leading up to this day of takeover, his buffoonery reveals imperial ambitions: Greenland, Canada, the Panama Canal. Trump’s mental aggrandizement demands the globe for its ballooning.

Conformity is the enemy now: normalization. Response, resilience, refusal to compromise principle or one’s own values — all such offer needed paths of resistance and forward-going.

“Never give in” necessitates acceptance of the irreconcilable.

Never give in to an impulsive — overly-generous — spiritually carried away — forgiveness. I understand forgiving others in order to free oneself; in general, this is good psychological advice, possibly good for the soul (though not for sure, as claimed, since the truth sets free in a more exacting spirituality); notably, such forgiveness for one’s own sake addresses neither the one who may or may not deserve forgiveness nor those besides oneself who have been violated. Never give in to an unearned forgiveness. Never forget.

I’ve touched upon the limits and requisites of forgiveness: here (Sunflowers) and here (Buber/Wiesenthal) — two of Poetry, Thought, Word Magick’s top posts according to Substack metrics — each of which brings up Simon Wiesenthal’s book, The Sunflower: on the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

Soyinka, too, offers discernment in connection to the act and idea of forgiveness.

The artist of You Must Set Forth at Dawn is an adventurous thinker and an activist fighting for freedom, concrete and creative — in other words, an artist. He’s no ideologue. At various times in his long life, he was imprisoned, exiled, and has had his books banned, yet he invariably places blame where he finds it; whether right or left, black or white, colonialist or nationalist, he is a humanist, and hates the tyrant. In another book of his, The Burden of Memory, the Muse of Forgiveness, out of such experience and commitment, Soyinka confronts glaringly what forgiveness truly involves, how often it plays into the hands of the oppressor, and where and when it can (rarely) arrive in good faith for the benefit of the victim — and of truth.

The back cover of Soyinka’s The Burden of Memory, The Muse of Forgiveness asks, “Once repression stops, is reconciliation between oppressor and victim possible?” What use is a question like this at the onset of unstable, indeterminable times, when the only firm expectation of the incoming regime is that it will shock-test our system of government and society? Anticipatory restoration — from where we are now, from where we might end up. Burden/Muse, published in 1999, collects three lectures given in 1997, the year after the establishment of South Africa’s post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Restorative justice requires restorative language, first: precision, truing the purpose.

Throughlines. Memory is history, history is memory, a people carries burden of memory due to historic oppression, “cultural and spiritual violation” within the psyche of nations, races, peoples; a section titled Memory: Conflict and Healing, for the burden persists, the violation persists, that’s the truth of the matter of a collective consciousness’ carrying, its source in memory, Truth and Source, urgent towards healing thus: Truth and Reconciliation. Yet, there’s that question, is it possible? how is it possible? for within the question, doubt, an implication of how inadequate “Truth and Reconciliation” is for justice, for the future, for the future just society; for the truth might do what it does to set the individual soul free, but what power does it have alone in the face of crime, in the face of terrible collective transgression? Disclosure of truth does nothing to ensure any fair and just reconciliation — there are incidents of forgiveness that are injustice itself! Certainly transgressors’ shows of remorse are often spurious, problem of the impossible testing of regret, one aspect of the difficulty here. Thus, reparations — reparations before reconciliation. Demanding atonement is humane, divine. Soyinka notices the religious-transcendental attainment of forgiveness, fine for preaching, but not for policy; so politicians have a different task than priests — and so too, the poets. The poet of a historically-burdened people, often transcendentally-inspired (and of priestly or monkish dedication to task), seeks earthly justice as a timeless value, as an eternal verity, and takes care to “minister to the pangs of memory.” Here, with literary attending to Memory, we are in the territory of Nabakov and Proust, aesthetically. Politically, Soyinka asserts that justice constitutes “the first condition of humanity.” There are crimes that need to be expiated in practice, whether or not any spiritual reckoning follows or precedes. To overcome hate in oneself is commendable and, likely, salutary. Yet, so long as oppression and the effects of oppression persist, it is misguided to attempt to overcome Hate of the oppressor ahead of the just necessity to overcome once and for all the oppressor’s Hate.

Drift. Soyinka is a freedom fighter and, in an artistic Life-Time of self-freeing, an individualist; he acknowledges the uses of revolutionary violence but spies out as well “psychopathic opportunists of a revolutionary struggle” in favor of true heroism, which is always a moral heroism first, the heroism of integrity and standing alone if need be. Politically incorrect (a label he embraced in the ‘90s) while anti-colonialist, refusing any form of rhetorical or ideological conformism, Soyinka notes the as-devastating impact of Arab-Islamic colonization of Africa in the centuries before Christian-European colonization, and then into his day as well dares to point his finger at African dictators who’ve desecrated the continent.

Between the time of his lectures and publication of The Burden of Memory, The Muse of Forgiveness, Soyinka had to endure the tragedy of president-elect Bashorun Moshood Kashimawo Abiola’s death. Chief Moshood Abiola won the presidency of Nigeria in 1993 with broad support, but the military dictator in power at the time denied the outcome (leading to a crisis that in turn had him usurped by another general); Abiola was imprisoned in 1994 for asserting his claim to the presidency. Four years later, Abiola died on the day he was to be released with all hope of becoming the nation’s rightful leader; although never proven, assassination remains suspected, likely by poison (there’s the reported collapse with teacup dropping from a lax hand), or possibly by beating. Both Burden/Muse and You Must Set Forth at Dawn convey how much this event impinged upon Soyinka’s heart and mind, indicative of the precarity of democratic hopes — and a good man’s life — amidst unconstrained power and corruption.

Humanism, humanity, the individual human: without specificity, the abstract is empty, unity en masse needs affirm the unit, identity, concomitant self-definition for the one and for the whole; Soyinka states, “we insist on the determinant and purpose of history as the human entity in and for itself,” and goes on to invoke W.E.B Du Bois’s “throbbing human soul.” The great evil is Denial of Humanity. Humanism is the moral driver here on earth, above religion with its zealotry inciting orgiastic revivals of destruction in every era (vide Christopher Hitchens’ God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything); that’s the spirit in which Soyinka irreverently lowercases the names of major world religions while capitalizing “the Orisa,” Yoruba deities of practical worship, emanations of the supreme divinity. Dehumanization — legacy of colonization and slavery — runs up-down the polarity of master-slave, bindings from both ends; to become what one hates reenacts the legacy; Soyinka recognizes that the African strongman for being Africa’s own has no greater right than the colonizer to trample his people; he calls them slave dealers and slavemasters who interfered with Abiola’s election and the people’s will. The only way to overcome, to get over slavery and its invasive memory, isn’t to become the master, the oppressor, but to get to one’s own human being, respect for humanity in oneself and the other. This humanism in action, in Hegelian resolution, opens from the creative — everything else is mere interchange within the same oppressive dynamics, and unfree. The poetic, perhaps in tension with the priestly and the politic, conceives a different, distinct forgiveness, a distinctive compensation; Soyinka praises the poetry of Léopold Sédar Senghor and Aimé Césaire, careful with distinctions, for tendering “a revaluation of neglected humanistic properties.” A critic for the single individual, Soyinka himself achieves his singular individuality, model of freedom. True Power.

Truth and Reconciliation

Soyinka inserts a desideratum: Truth, Reparations, and Reconciliation

True Source. The “poetic” voices echoes and trickling, the rudiments of a thinking — poetic origins of humanist thought arising from poetic freeing, the singular operations of creativity. Soyinka says, “Style, in such circumstances, becomes a critical statement of intent, even in its groping, inchoate stages, a manifesto and shared instrument of self-liberation.”

Césaire “sweeps up all the negative imagery that has ever been bestowed on his race” and transforms this hate through “the magic of the creative intellect.” I can’t help noticing here Soyinka’s use of variants of P,T,WM’s three terms.

magic — magick creative — poetry, making intellect — thought

To release and set right, set upright as “an insurgent weapon of self-recognition, affirmation,” all the negation of the downtrodden, so-called, Soyinka realizes Césaire in annunciation of “Those without whom the earth would not be earth… ”

Among the Orisa, Soyinka maintains a fascination in both books with Ogun, “the god of war and destruction” — Strife! — “of the lyric and creative spark, a protagonist into unsuspected realms of existence and consciousness — including the world of moralities.”

Here I lay down a couple more of Soyinka’s phrases, be they as sunflowers, marigolds, or ram’s horns in essential antithesis to slavery and tyranny: “a mantle of humanity that excluded none” and “universal affirmation of a humane oneness.”

Do you need a Call to Action? Setting forth is action. To dwell as you were is perilous in times of unchosen change. It could come daily, it could come once in a lifetime, the beckoning moment. Heed its “must” for warning, for portent, or for guidance, as a word to the wise, a hint from someone — a loyal friend — with good will for your escape, for your making your move, for your staking your claim.

You Must Set Forth at Dawn…

Indeed, the internal horizon is made objective, external — though action. Externalize your truth.

another in-edit typo (my keyboard x is glitchy) — eternalize for externalize

There’s also the category of the “world-historic,” as well as the operational particular that it is not only a category, but a plane, a plane for action; in mind of that, within time and yet on an order above the times, the court of the “world-historic” ascertains, passes judgment, renders a verdict (right or wrong side of history). There are indeed irreconcilable perspectives, realities, truths, certainly POVs can stand in hopeless opposition, yet not all are equal on the historical plane, some are lacking, perspectives have greater or lesser scope, or depth, higher and lower condition a viewpoint’s essence as much as its sweep; clarity, obscurity, and obstruction determine accuracy of interpretation; historical time assays truth v. the opinion of mortals, true power v. brute force, truth-tellers v. liars.

“We are engaged in a war of narratives, of incompatible versions of reality, and we need to learn how to fight it.” — Salman Rushdie

I’m still spiraling from here: Ephemera Infinity Spiral 9.17.24

Never resigned, never reconciled to the same age-old cowardices of ways-of-the-world untruth and inhumanity, creativity dares to think again, think over what is needed — for action, for setting forth. Sequence of crystallization: intimation, thought, reality. In the coming age of geopolitical scramble over spheres of control of earth’s resources, all hope for human rights and freedom depends upon thinkers and artists (whatever their vocation may be) consciously creating — competing for — and fighting for — an open global culture of the future.

Here, again, is Salman Rushdie at the PEN America Emergency World Voices Congress of Writers, in May 2022 at the United Nations. Since then, Rushdie (living under an Iranian fatwa calling for his death since 1989) was stabbed twelve or so times in New York state by an Islamic extremist — and lived to write about it.2

“Meanwhile America is sliding back toward the Middle Ages, as white supremacy exerts itself not only over black bodies, but women’s bodies too. False narratives rooted in antiquated religiosity and bigoted ideas from centuries ago are used to justify this, and find willing audiences.”

& yet

“…the powerful may own the present but writers own the future, for it is through our work—or the best of it, at least, the work that endures—that the present misdeeds of the powerful will be judged.”

More at: PEN vs. Sword

RIP David Lynch. Relevant to my fear here of having paraded a white hat, I’ll take Slavoj Žižek’s account of Lynch’s most dark and daring nonconformism: David Lynch Is Dead, But His Ethics Is More Alive Than Ever. Meanwhile, my and my daughter Hero’s Llama comic strip has been for us an ongoing attunement to everything we were able to learn of Lynch’s creative practice for “The Angriest Dog in the World.”

David Irving, Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich. The sentimentality of that afterlife “somewhere” in this passage is especially grotesque as applied to the foremost propagandist of mass murder.

Salman Rushdie, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder