He was truly alone. Still, there were people in this town who cared for him. And let him be. He roamed. The forest, the hills. High lands brought him brow to the sky, deep breath through the nose - solace to go where he liked. Low ground, he walked the railroad tracks, way to avoid encounters with white people. He was always sure-footed, even in shoes, never mind pebble, stone, fallen limb, bramble or rabbit hole. There was heat in summer, he was used to that, humid air sticky with insects, great pockets of gnats. Then snow and ice in winter, he’d had time to adapt already, and here there were homes where it was warm and he was welcome. He fished the river. Light through the leaves at dawn or sunset crimsoned his path. Although he had a room, he’d sleep outside at will or in a neighbor’s shed where, through uneven slats, you could watch the stars on their roll. Many an hour he enjoyed smoking on a hammock in peace.

The kids loved him. He taught them to fish and to hunt, how to make and shoot arrows. How to smoke out a hive and gather the honey, how to recognize which plants and berries out in the woods were safe to eat. How to find their way in the forest. He gave them adventures, nurtured the daring spirit of childhood. It must have stuck: one of the boys he spent time with grew up to become a dashing aviator, a pioneering Tuskeegee airman, whose ten-city tour in a rented biplane paved the way for the program to allow blacks to be trained as pilots for the Army Air Corps as World War II loomed. A part of the community, he mingled with professors and intellectuals and poets, and he learned to read, and these people listened to him and to his story; most of all, though, he was close to the children, until at last it came to the point that he had to explain to the boys one day (after much time playing with them), “I am not a boy, I am a man.” I can’t forever play with you. And once, I had my own children, long ago and in another land, and a wife, and they’re all dead, and then another wife, and she too is gone. Besides, he had adult duties: he did odd jobs at Mammy Joe’s store and worked at the Lynchburg tobacco warehouse - fellow workers remembered how he could get up to the higher racks without a ladder, climbing the poles. With friends of all ages, he’d sing nursery songs and spirituals; outdoors on the heights he’d listen to the women’s choir, their hymns sometimes overtaken by a train’s piercing whistle. He’d drum and dance and chant his own forest songs around fires he and the men and boys built together; sometimes, in a somber mood, he’d play a molimo fashioned from local maple wood and a dog of the neighborhood would lean its flank against his legs.

South Winds The Pennsylvania Train escort down to Virginia ...talks/ about Lynchburg and the seminary college just across the road from Professor Hayes' home. Talks about Durmid Hill: woods, cows, pigs, dirt roads. Boarding the Southern, they enter/ the Jim Crow car THE HOUSE ON DURMID HILL ...in the buggy on his way to the Hayes home, Gregory, a child beside him so full of questions like his own son. The big yellow house settled in a cluster of trees, seams bursting with welcome. ...And Mary,/ expecting another child, always says, Room for one more. Screech of the front porch swing. The big oak in the front yard, The big back porch with the long table for summer's meals buttermilk the children churn Ota's Virginia Into the woods with the boys, fishing on the river, like home... - excerpts from Ota Benga Under My Mother's Roof, poems by Carrie Allen McCray

If the people of the community took him in freely, and he found himself relatively free here in Lynchburg, still he felt his own difference and that his life could never be the same as theirs and he would never be the same as he once was. At least on these hills a shared humanity was more real, more reliable, than when he was put on display in a cage in the Monkey House at the Bronx Zoo and, before that, was sent to live in New York’s American Museum of Natural History, a walking exhibition; all this, following the reason he was brought to these shores in the first place, along with others of his and neighboring tribes from the Congo and of other tribes and ethnicities and body types from around the world: to be an anthropological curiosity for the St. Louis World’s Fair.

What happened to Ota Benga is a story of a human being dehumanized, objectified, and forced into the circus/freak show that has been an inescapable part of American popular culture since before Barnum, along with trash science and racist politics.

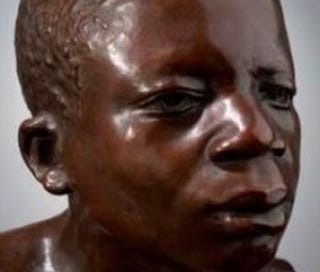

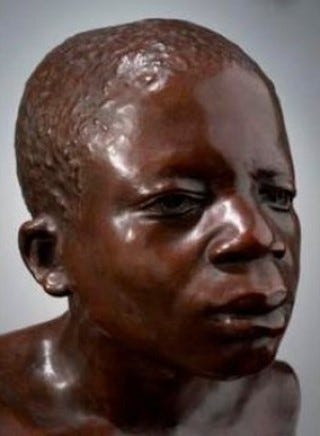

Nevertheless, he is irreducible to any image or framing. There are quite a few photos of Benga as the subject of spectacle, yet not a single one has been discovered of him in Lynchburg, the one place where he was truly appreciated and loved for years. That absence of captured image is telling. The plaster bust shown above is at least useful for its carrying evidence both of his palpable, dimensional embodiment as well as of the abuse of his personhood, taken from life at the aforementioned St. Louis World’s Fair (one of a series of busts made with every attention to phrenological measurement and ethnic categorization) and preceding him to NYC’s Natural History Museum where it remained two decades beyond his lifespan until it was gifted to Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art in 1936. As for his image in Lynchburg, he is held in cherished generational memory and, while there is no photograph of him, there is a picture of a group of children known to have played with him and one of the boys is holding a spear. This is a visible trace of Ota Benga’s presence. Perhaps, in sensitivity to whatever sense of soul-stealing might have lingered with him or them as to making him a subject of photography after all he’d been through (which sense would be a matter of higher ascertainment, not a superstition at all), the people around him in Lynchburg respected him enough to be careful of repeating the trauma of objectifying him once again.

Ota Benga’s history begs to be well-known; in defiance of his exploitation as a human exhibition, his story needs to be told in such a manner that his spirit emerges before and beyond and under and over - if also necessarily through - whatever image is his, however cinematic his drama: his presence and reality coming through the damage. Like Heraclitus emerging through time and fragments of text, Ota Benga emerges through every imposition of othering and stereotype upon him; no projection sticks to his resisting, resilient substance. Any approach to him must honor the echo and magick of how personality endures through all destructive forces of nature and humankind.

Stories for the Story

Every story is personal.

It’s been about seven years or so since my friend Robert Zweig first brought Ota Benga to my attention. Rob had visited the Bronx Zoo throughout his life and, indeed, up to the pandemic, he and his wife Jayne took walks through its grounds more than once a week. I won’t forget the profound shock that was still apparent in his demeanor some weeks after he found out that a Congolese forest man had once been placed in a cage there with an orangutan to symbolize for the public a “missing link” (giving the new zoo with its global reputation, in 1906, its biggest draw yet); there was a quality of betrayal in his response to this discovery, what with his lifelong familiarity with the institution and its spaces. This is the betrayal every person wishing to inform themselves in good faith experiences when taking a clear-eyed look at U.S. history. At the moment of his conveying the story to me - through our questioning of Why don’t more people know about this? Was the incident covered up? - inevitably, it seemed, we envisioned a feature film. We’ve partnered in the research and development of this vision ever since. At another time, I’m sure, I’ll relate my own story of what principles of art and ethics have confronted me in my attunement to Ota Benga. As professor of English at the Borough of Manhattan Community College of the City University of New York, as the memoirist of Return to Naples: My Italian Bar Mitzvah and Other Discoveries , Rob Zweig’s literary orientation to personal narrative lends special access to a daily life (banality of evil) perspective on the primary event of Benga’s victimization.

From here on out - in keeping with this Substack’s mission of sharing what’s behind the creative process and offering a glimpse of the pathways for realizing a vision in the world - I’ll keep you updated with our efforts in bringing such a tightrope walk of a project to fulfillment.

Carrie Allen McCray, poet of the work excerpted earlier, was born into the family who had taken Ota Benga into their home. Her mother, Mary Rice Hayes Allen taught at the Virginia Seminary, now Virginia University of Lynchburg, an HBCU, and she and her first husband - Professor Gregory Willis Hayes, president of the seminary - joined the nationwide protest against the exhibition of the pygmy at the zoo and, in time, brought him to Lynchburg. As a writer who started a prolific literary career late in life, in her seventies, McCray in multiple works tells her own stories of her generous and vibrant family, and household. She only knew Benga until she was three and depended on her older half-brother Hunter Hayes to enhance her toddler mist of memory. Under My Mother’s Roof took the longest of all of her books to complete; she always talked about how she had to “get it right” to its editor, the poet and composer Kevin Simmonds. At last the book came out in 2007, one year before her death at 94.

Her poetic understanding gave me an angle of access to Benga’s interiority for the work and, as well, drew me to Lynchburg: I finally made the trip this spring.

My great new friend, Ann Van de Graaf, arranged everything. She is a font of stories and joyous artistic fecundity. For close to a decade she maintained Africa House, in the neighborhood of Virginia University of Lynchburg, as her own art studio and as a gallery and community space for African and African diasporic art, culture, and traditions. She knew Carrie Allen McCray. She herself is a driving force in remembering Ota Benga: she organized, in 2007, an international conference titled, Lynchburg, Ota Benga, and the Empowerment of the Pygmies, which included a Pygmy delegation; and she co-sponsored the establishment of a Virginia Historical Marker for Ota Benga in 2017.

We gathered at the marker for a ceremony in honor of Ota Benga on March 24th, 2022 - the plan is to have an annual memorial there as close as possible to the vernal equinox. It was then I met group of people whom I feel safe in describing as an informal alliance of those who, with attentive accuracy, care deeply about Benga’s spirit and legacy. (This is in contrast to NYC and the Bronx Zoo, which only in 2020 issued an official apology and has always begrudged any sort of confrontation with this historical outrage). Perhaps, with individual permission, I’ll go into further detail of their stories at a future date; broadly, in Lynchburg there are active ties and a crisscross of memories of the actual presence of Benga handed down through parents and grandparents, through institutions such as the seminary, now university, and the church where his funeral was held. After the program at the marker, we walked together and placed flowers on his purported grave, identified at this point only through just this sort of passed-along personal, memory-based, on-the-ground surmise. The site has a plaque on a chain surrounding it but no stone monument.

Anne Spencer House and Garden

Here, the walls sing. So many lasting voices, historical names, its own source of living history. Anne Spencer had five poems in The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), a major anthology of the Harlem Renaissance as it was happening; her home - so far South of New York City - was a salon for Harlem Renaissance figures, and more, beginning before its advent. A biography of her aptly takes one of her phrases as its title, Time’s Unfading Garden (from a gift “rime” she wrote blessing a friend’s baby born on Christmas). The museum is under the loving care and advancing vision of Anne Spencer’s granddaughter, Shaun Spencer-Hester, who also reveres her father, Chauncey Spencer, that earlier mentioned Tuskegee Airman, featured in the Pioneers of Flight gallery at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The house reverberates with people of the past as if nothing could be lost so long as it is refreshed with open doors and the garden’s bloom - which it is. Stories upon stories needing to be told. Visitors through the years included Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Langston Hughes, Zora Neal Hurston, Paul Robeson. It was there James Weldon Johnson would’ve communed with Ota Benga. Likewise, W.E.B. Du Bois - there, or at Professor Hayes’ home, or at the seminary: Benga contributing to the imagination of the Harlem Renaissance and to the politics of the Pan-African movement.

Anne’s husband Edward built her a writing cottage which they named Edankraal (for Ed and Anne and also that insinuation of “Eden” combined with the Afrikaans word for “enclosure,” kraal). Inside, even now, you can align your thoughts with the cumulative charges thrilling the space within which a genius poet habitually preserved her creative solitude - sanctum for the daily task of a mind freeing itself.

excerpts from "Ota Benga at Edankraal" by Yusef Komunyakaa

Not sure of the paths & turns taken, woozy in a swarm of hues, he stood in Anne Spencer's garden surrounding the clapboard house, but when she spoke he came back to himself. The poet had juba in her voice... Her fine drawl/ summoned rivers, trees, & boats, in a distant land, & he could hear a drum underneath these voices near the forest. The boys/ crowded around him for stories about the Congo, & he told them about hunting "big, big" elephants, & then showed them the secret of stealing honey from the bees with bare hands, how to spear fish & snare the brown mourning dove. ...

Exemplary of a way of receiving the materials of violation handed down sorely to us by history and transforming them into honorable, tender art: Fred Wilson’s 2008 bronze sculpture cast from the original St. Louis World’s Fair life-cast.

This came after Wilson (born in the Bronx) discovered the series of plaster busts classifying “types” of so-called primitive peoples hidden away in the Hood Museum’s collection; he presented several of the busts as part of his 2005 installation at the museum interrogating the act of seeing and the imposition of objecthood, titled So Much Trouble in the World - Believe It or Not!

Ota Benga’s story, in particular, wouldn’t let him go and so later Wilson took his act of reclamation an extra step, creating a unique bronze sculpture. When shown, the piece has a white scarf covering where the original label had been, in favor of words the artist engraved on its wooden base: “I’m the one who left and didn’t come back.”

May I share this post on a local Lynchburg based substack called “Bridge of Lament”? I want to highlight Ota Benga this month and I came across this post and it’s beautiful

Superb account and a beautiful honor of a man not only wronged by America, but simply humiliated by the nasty virus of racism. Your words renew some dignity and imbue empathy here, thank you brother. You continue to teach and inspire.