For the full is thought

Parmenides, fragment 16 (David Gallop translation)

The full. Thought-through, and filled with thought, filled as thought, consciousness. The full is plenum, full of what is, same for all — common to all —everything is full or what is fills everything (as with fragment 8.24, is all full of what-is).

Alternative version (by T.M. Robinson, my go-to Heraclitus translator): “For the plenum is ascertainment.”

Early on in this space (another time, another context), I delved into the word:

Incipient need-naming: desiderata of creative life, to think again, to think over, inclusive society worldwide, universal individual human rights, consciously, to build towards an open global culture of the future. Avoiding pitfalls, time again — time anew — to think through. Sense through imaginative ideal to practice, practical shaping, to clarify, to make vivid in conflict or peace real possibility, vivifying

Think globally, and despair? Or hope? The politics and poetics of making dreams realities. & what to do (in rage and outrage) before the living vivid intolerable? — so present. Here’s1 Salman Rushdie, who would know…

A poem cannot stop a bullet. A novel can’t defuse a bomb… But we are not helpless. Even after Orpheus was torn to pieces, his severed head, floating down the river Hebrus, went on singing, reminding us that song is stronger than death.

We can sing the truth and name the liars.

Crises, flickering flames vs. the unwavering real, the sun behind the sun

Some artists scoff at the eternal. Joyelle McSweeney, for one, dazzles in the antagonisms of totalizing anguished present(s)/presence against any escapist transcendence. Often as itself a moral stance, as ideological righteousness, as the ethical here-and-now, devotion to the magic or anguish of the moment, this moment and its surge, rejects the Absolute — and its mystic, totalitarian precipice for thought and action. You’re a dangerous person if you see through your thought to action. The only justice or passionate response is of the moment, timely. The only problem is: that’s not true. The ephemera spiral goes just fine for and through its moment, but I insist its action (spiraling) is infinite. Despite some recent2 political denunciations of Antonin Artaud’s primal, mantic scrawl (he was a man tortured by untimely intimations), I’ll go back to Artaud, always. &, as well, Deleuze-Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus (its materialist interpretation of libidinal forces certainly quivers with perpetual motion, desiring-machines). Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence is a physics (rather than metaphysics), and materialist, made upon a physical argument. & I’ll go back to the classics, which lastingness actually has its basis in the fact that they aren’t and never were “of the moment”; most canons are chock-full of works transgressive to the historic times they came out of3, and any stodgy or ambitious canon-guarding is doomed to fail the test of time, as each work creates and recreates its own canon according to its time-transcendent qualities — much in the manner of, as Borges pointed out, writers creating their own precursors.

"Nothing Lasts Forever" by Echo and the Bunnymen

As mentioned last time, my youngest just started his freshman year at college. Gryphon is studying film at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. As a family, we’ve always doused ourselves in movies. As one of the last things we did together before dropping him off, Gryphon and I watched Sorcerer (1977) by William Friedkin, starring Roy Scheider (footnoted last time for his role as Joe Gideon). It’s a masterpiece. Its beside-the-point title is the name of one of the jungle-slogging trucks featured in the story (the other truck was “Lazarus,” also kicked around as a title); even though nothing supernatural occurs in the film, Friedkin admitted there was a marketing connection to his fame from The Exorcist in the choice, which he said was ill-advised on the one hand, but at the same time justified by the overriding theme: Fate is an Evil Wizard. As convoluted as that may be, it is indeed what makes the film great — there’s no flinching at the fate of the characters. Friedkin is again astutely subtle in the interpretation of his own work when he denies that Sorcerer is a remake of 1953’s The Wages of Fear; rather, he is rendering his own take on the source material, Georges Arnaud’s Le Salaire de la Peur, a novel based on the gritty, freedom-fighting, resilient if bitter French author’s own experiences in South America in the late ‘40s. Associations abound. There’s Thunder Road with Robert Mitchum, who shows up in Scorsese’s Cape Fear, which we also watched (re-watched) during Gryphon’s last couple of weeks at home; these, relevant to our seeing an excerpt of Mitchum in Night of the Hunter before a screening this summer of Do the Right Thing at Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, prep for Bill Nunn’s rendition of the “Love and Hate” soliloquy as Radio Raheem (Manya, Gryphon, and I created a new tradition for the three of us starting his senior year in high school in which we met most Tuesday nights at Alamo in Arlington). Sorcerer in its nature — along with its grueling (some would say reckless) filmmaking ethos — is a precursor to Fitzcarraldo (of course, Werner Herzog is a precursor to himself, film-to-film), and if there were a “making of,” it would be parallel to Les Blank’s documentary, Burden of Dreams.

Not surprising given his upbringing, Gryphon’s taking a course called “Ancient Epic and Gangster Film” offered by Wesleyan’s Classics department. They’re reading Emily Wilson’s new translation of The Iliad. I couldn’t resist being the sort of dad who has to share something of his own enthusiasms and so made sure he had a copy of Alice Oswald’s Memorial: A Version of Homer’s Iliad4 in time for his class.

Here’s a video of Alice Oswald and Emily Wilson in vehement discussion just last year when the translation came out: The International Library: Emily Wilson on The Iliad with Alice Oswald

In mind of the living vivid, even amidst death: Oswald’s Memorial. War and its horrors, rage — sung, at the beginning of poetry.

Alice Oswald takes a singular path into the lucidity of Homer’s world. For the book’s introduction, she describes her orientation in the following way:

"This is a translation of the Iliad's atmosphere, not its story. Matthew Arnold (and almost everyone ever since) has praised the Iliad for its 'nobility'. But ancient critics praised its 'enargeia,' which means something like 'bright unbearable reality.' It's the word used when gods come to earth not in disguise but as themselves. This version, trying to retrieve the poem's enargeia, takes away its narrative, as you might lift the roof off a church in order to remember what you're worshipping."

Enargeia

The intention to reactivate an ancient poem’s enargeia captivates me in my own long pondering of the word, which I’ve steadily understood — not in contradiction to Oswald’s poetic understanding, but in further conceptualization, and perhaps politicization (its politics aside from poetics, aesthetics) — as “self-evidence.” Indeed, the word has its echo in: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The U.S. Declaration of Independence utilizes “self-evident” as the undeniable reality of enargeia, as an argument in and of itself out of common sense, the universal, the truth in its own light, a bright unbearable shining. Always thought I’d do an entire entry on enargeia as an epistemological exaction — and still might (though this probably covers it). Like several Greek words, such as logos and kairos, its generative allure tugs at my thinking.

Narrative-stripped, Oswald’s book hinges on atmospheric diffusion of the essence of battlefield tragedy: the spilled blood of each individual fallen soldier. She translates only the similes from Homer’s epic, vivid images, while rendering long lists of names, all caps names, of the warriors who died in battle, and brief bios of said warriors (shorter than obits), plus the moment of their deaths. Spare as it is, the book is filled with action: violent death.

What’s left without a war’s overriding story, its history, its context? Slaughter. The eternal waste of war. Oswald shows a life and a death and, within the poetic soft light and natural elegiac rhythm of similies in stanzas repeated twice, a personal quality flares. Here’s how she brings the first to die at Troy, PROTESILAUS — “he died in mid-air jumping to be first ashore” — home to us…

He’s been in the black earth now for thousands of years

Another anachronism, connecting the ancient world to ours, has Hephaestus “like a lift door closing” whisking a son of one of his devoted worshippers out of the way of a flying spear.

Spear-swift, we enter into the lives of the listed, named dead and we see the moment of death amidst crisscross of weapons and projectiles, mortal switch from on to off of being and not being, “Someone was there/and the next moment no one”; and then poetic repetition, “Like when the wind comes ruffling at last to sailors adrift”… and poetry itself somehow gets at the way a life leaves its traces (cf. Sappho’s “Someone, I tell you, will remember us, even in another time”). How and what are these traces? Enargeia names that afterglow.

Another line to mention, about a soldier’s young bride who must sleep the rest of her nights in widowhood: “Poor woman lying in her new name alone.”

With its action restricted to graphic fatal blows, the poetry remains epic, for the smaller stories of individual life and death yet depict an interplay of heroism and cowardice, of baseness and nobility (Homer notably honors the flawed humanity of both sides, never dehumanizes the enemy), and it matters how these men conducted themselves, it matters through millennia, and so Oswald’s minimalist piece isn’t simply an antiwar lament over those who’ve fallen in battle, but it is indeed a monument in keeping with its title.

Further in her introduction, Oswald reveals a key aspect of her artistic method — an operation available to anyone who gets that it’s possible. She activates a kind of sight through closeness with the language she’s working with; in intimacy with Homer’s words, she says, “I use them as openings through which to see what Homer was looking at.”

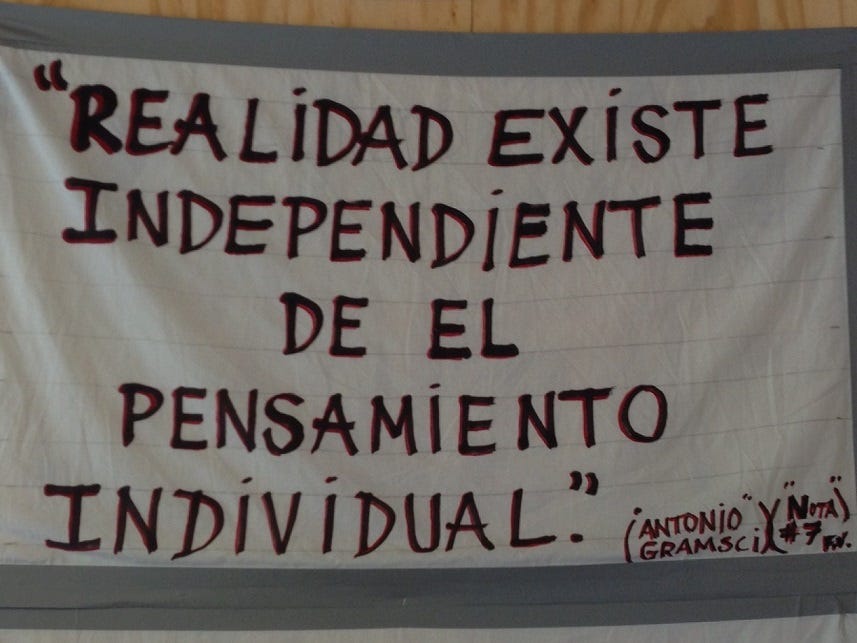

Greek words — words of whatever language — can be scopes for seeing-through, seeing into different times, different places. Obviously, you can see as the writing itself what another has said, but through the words you can see what was seen for the saying (I think Samuel Beckett alludes to this as well with Ill Seen Ill Said); you can align your mind’s eye with the telescope (or microscope, or kaleidoscope) of an author’s words and see the same, “see what Homer was looking at,” and say it for yourself, say it your own way, believing it as you see it. All this indicates that there’s something there, independent of both writer and reader. Always there’s something there, beyond one’s force, frame, or control.

Perhaps that’s the translucence of enargaie, the enabling of perceptibility, the abiding in clarity of existing things — material and immaterial. Clarity itself is invisible, transparent, like a veil but the opposite of a veil, for it’s not a covering but it’s why what exists is discoverable, awaiting acknowledgement.

Speaking of translations (Parmenides, Homer), one of the most exquisite poetry readings I ever attended was at the “In Your Ear” reading series at DCAC, 2005? 2004? I remember poet, scholar, and musician Tom Orange letting us know that Caroline Bergvall couldn’t make it as scheduled, but she sent a recording: her voicing the extant English translations of the opening tercet of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, ché la diritta via era smarrita.

We all listened in the dark, in the tiny black box theater, mesmerized by the rhythms, repetitions, and variations. In the end, I was particularly excited by its culmination with the translation I relied upon in facing pages to the Italian, Allen Mandelbaum’s. When I had journeyed half of our life’s way/ I found myself within a shadowed forest,/ for I had lost the path that does not stray.

di nosta vita our life's way

Most variations include that unexpected intrusion of the universal plural from a singular subject.

Not sure if this is the exact recording we heard that day, but here’s what I found today for your transported listening:

Caroline Bergvall’s Via (48 Dante translations) mix w fractals

Also recommended: Babel: an Arcane History by R. F. Kuang, a masterful anticolonialist fantasy of translation, etymology, and word magick set in 1830’s Oxford. She’s only 28! — and this is a #1 bestseller after she’s already met acclaim for her Poppy War trilogy (its first book acquired on her twentieth birthday). A prodigy of language and intrigue.

Always looking towards the rays of the sun

Parmenides, fragment 15

PEN vs. Sword, remarks at the PEN America Emergency World Voices Congress of Writers, May 2022 at the United Nations.

E.g. Artaud and his Doubles, Kimberley Jannarone, 2010

My own “Canon of the Free Spirit” (or anti-canon) is sought here: The Free Spirit (ebook). Also, click for my abandoned Tumblr on the subject: Free Spirit Anti-Canon

Mark Jickling brought Oswald’s book to my attention a number of years ago; he also created a video on Heraclitus I posted in this space awhile back: Thunderbolt at the Controls

so great! all of this.

yes to this line you highlighted

“Poor woman lying in her new name alone." wowza ! and the "our" lives in dante. yes, very beautiful