Last week I revisited Lynchburg, Virginia for the second annual Ota Benga Memorial Service: “We Remember Ota Benga.”

This event was at the historic Diamond Hill Baptist Church on Sunday, March 19th. After attending the first annual service held at his marker in Lynchburg’s Seminary Hill neighborhood last year, I wrote about how the community I met on that trip influenced my understanding of Ota Benga’s story.

My screenplay writing partner, Rob Zweig, and I are as committed as ever to finding a way to tell this story as a feature film with utmost artistic conscience (as discussed in this earlier Substack article). Meanwhile, the community I found in Lynchburg mushroomed over the past year. Reformulated as “The International Ota Benga Memorial Committee,” the group has new goals and new energies thanks to Dr. Myra Gordon’s arrival and fresh support of Ann van de Graaf’s decades of tireless leadership and expertise on behalf of Ota Benga’s legacy.

I hope to be able to share a link soon with video of the program at Diamond Hill because it was an absolute celebration of the art and thought Ota Benga inspires: concise talks on Benga’s time in Lynchburg, on the Mbuti way of life in the Ituri rainforest, on the lasting lessons this story has to offer today’s youth; deep sadness in song and great exuberance in drumming and dance (this latter with young dancers from the Kuumba Dance Ensemble); a poem in Kiswahili from Congolese committee member Francine Baruti with her beautiful English translation; and soaring, stunning prayers.

Here’s what I offered, a poetic salute, as evocatively phrased by Ann van de Graaf when she asked me for some work for the occasion.

Beneath the Vines

Home is the forest your only home you dance your joy Ota Benga according to the play of shadows what light gets through the canopy everyone else is afraid of the dark your afterlife is this dance beneath the vines you were taken from your home you were taken from the forest why is there joy to know of you somehow Ota Benga? this afterlife is your dance beneath the vines defiant of violations to your living hours ours is the love defiant of violations to your living hours ours is the love, responsibility to honor you through humid, dripping, writhing vital... The clearing is destruction. your impenetrable forest is safety of home lush lush righteous anger this afterlife is your dance beneath the vines around the fire with fire in your eyes was it here or there Ota Benga death and life where a stream you fished held the setting sun in its luminous reddish-orange cradle? Virginia woods could never replace your Congolese jungle its fertility and heat nor tobacco factory rafters Anne Spencer's garden Mammy Joe's hayloft where you left your blood wild honey Molimo you had ears for the joy of the forest where you left your blood wild honey Molimo your afterlife is this dance beneath the vines Ota Benga, didn't one of the Lynchburg girls see you stop and place your forehead against the trunk of an ash tree? didn't she see you standing there with your head against the tree? you stood without moving for a long, long time as dusk turned darker and darker into night.

The next day our committee held a private ceremony at White Rock Cemetery at the site where Ota Benga’s grave is thought to be (there are no official records of his burial; he was funeralized at Diamond Hill Baptist Church).

Meaningful coincidences shuddered through us in the cool of the day.

Reverend Chris Roussell of St. John’s Episcopal Church presented a rousing prayer-poem in touch with Ota Benga’s spirit as wind in the forest. He and I discovered we had New Orleans in common, as well as poetry and writing (he studied with Andrei Codrescu at LSU).

Next, Hunter Hayes III - as if it were planned - sounded the murmurs and howls of the wind as part of a recording he played, his original composition, accompanied by live molimo. Gusts followed upon gusts in spirit and music.

Hayes, an Emmy-winning composer, jazz musician, singer, and saxophonist is the grandson of Hunter Hayes, one of the boys who followed and played with Ota Benga in Lynchburg, learning skills of the Congo. Also, he’s the great-grandson of Gregory W. Hayes, buried in the same spot, the prominent leader of the Virginia Seminary who invited Ota Benga to come to Lynchburg and live in his home - a man central to the vibrant cultural milieu welcoming the traumatized Mbuti tribesman into its midst.

When Hayes blew the molimo - both at the beginning of the service in the church and again at the start of the graveside ceremony - I heard the blast of the shofar.

Indeed, Hayes intrepreted the molimo call with a sequence of blasts surprisingly reminiscent of the blowing of the shofar. Given that Egyptian sources indicate a continuous Mbuti culture going back 4500 years (along with ancient Greek and Roman depictions of “pygmies” varying in their blends of factuality and myth), it’s fun to imagine a cross-cultural common source for the shofar and molimo sounding alike - either through actual encounter or through antique, universal back-of the-neck chills coincidence.

Hayes next showed how mellifluous the molimo could be when enfolding his playing into the recording of his composition for the wind. I don’t think my phone quite captures it here, but maybe some sense of the music comes through.

Within these past couple of weeks, Hayes built the molimo with reference to the one Ota Benga is known to have constructed at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Up until now I thought these instruments were made of wood, but it turns out it is just as usual for them to be put together by found parts.1

Hunter Hayes III, musician and artist, created a beautiful artifact as well as a playable instrument for the occasion.

I wasn’t the only one who assumed the instrument could only be fashioned of materials from the forest. Jazz critic and music scholar Ted Gioia tells of another makeshift molimo in a recent post from his Substack, The Honest Broker: Parable of the Molimo

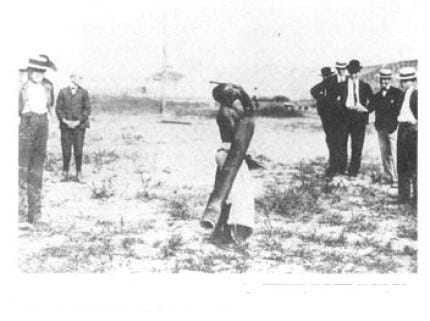

As you can see from the old photo of Ota Benga above, the drainpipe molimo goes back long before Colin Turnbull (who never mentions Ota Benga in The Forest People, by the way, and seems to have skipped the whole generation-long period of atrocity under Leopold II when giving his account of what was known of the Mbuti pygmies before him).

Momentous and a moving reclamation of humanity in a brutal world. You have led us into deep cotton. Thank you Magus. I look forward to what is to come on all the work you have done for and about Ota Benga...and the mirrors you want us to look into.