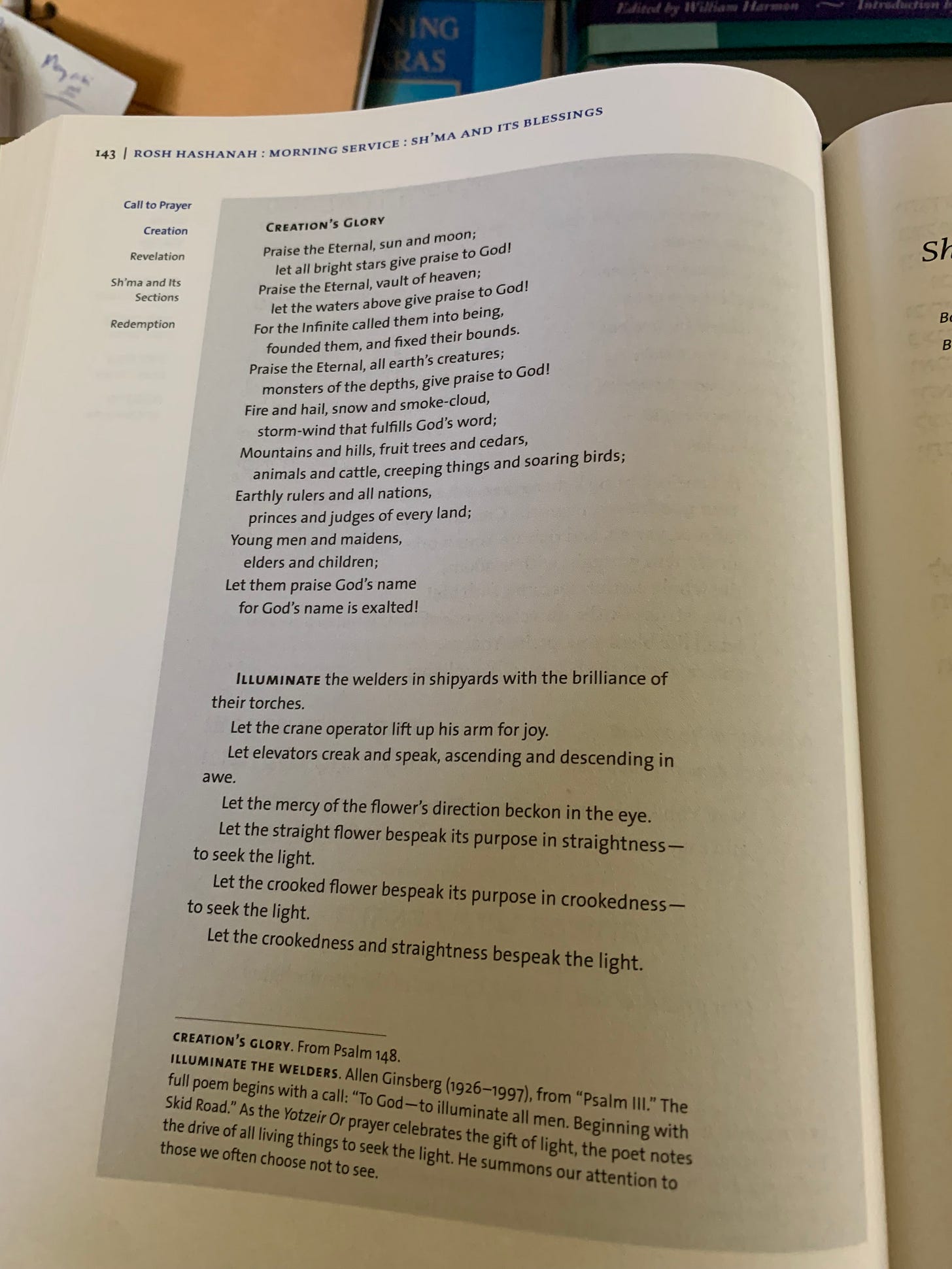

In the latest North American Reform Judaism prayer book for the High Holidays, a part of a poem by Allen Ginsberg bursts forth, crooked and straight. Published in 2015 by the Central Conference of American Rabbis, Mishkan Hanefesh: Machzor for the Days of Awe - Rosh Hashanah spills over with modern poetry (and all sorts of other writings old and new), alongside the prayers.

It’s exciting to find within the pages of a prayer book vigorous affirmation of individualized winding.

Illuminate... Let the mercy of the flower's direction beckon in the eye. Let the straight flower bespeak its purpose in straightness - to seek the light. Let the crooked flower bespeak its purpose in crookedness - to seek the light. Let the crookedness and straightness bespeak the light.

This year I didn’t attend Rosh Hashanah services in person, semi-following along at home on Zoom instead. (I’d had what I thought would be a negligible operation on my tongue the Thursday before, but the impracticality of eating and speaking - not to mention appearances, the wound’s gruesome swelling and blue-black-bloodred discoloration - took its unexpected toll through several days of alternating humorous and horrible makeshifts for normal functioning; I know more than ever now, with relevance to words formed in the mind as well as shaped into sound, how much the tongue - like they say of an octopus’ tentacles - can be experienced as a kind of brain, an intimate extension of perceptive apparatus. Words and sense of the tongue.) Mostly, I went back and forth through the book; I re-read that which I remember reading to myself the year before, quietly amidst the crowd. Then, and again this time around, to myself, I could hear Ginsberg as he is. Yet, I recall how the congregation read his poetry out loud last year, like a prayer, as a call and response.

Ginsberg’s poem was read aloud in call and response with the same tonality as the prayers of the service: the religious tonality of a chant, laden with the (albeit sacred) dust of the ages…

On paper, I relish the juxtaposition of sacred and secular. Vital, contemporary words of radical, uprising spirit-freeing impetus placed with traditional, classic prayer, holy thunder. Yet, in the air, it was as jarring as a church bell - the rampant, relatively new made venerable through an old-style tone, through being intoned.

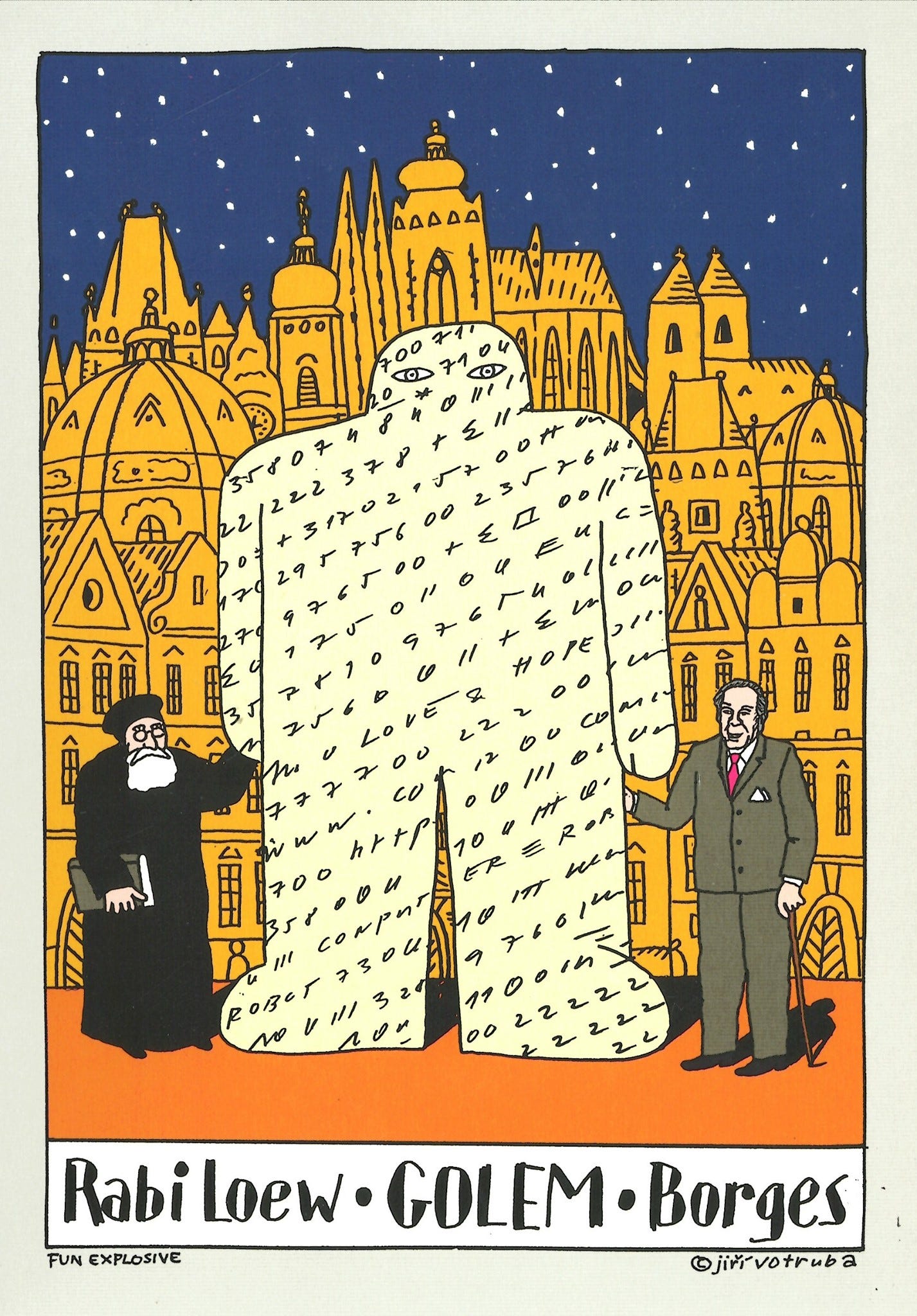

This appreciation of the new - of innovation, and the freshness of each day, each year - of contemporaneity whenever that is - is part of Jewish tradition itself. The Jewish sacred is the old and new together. Indeed, the term “Old-New” is a mighty Jewish hyphenation; the Old-New Synagogue in Prague1 dates from 1270 and has been referred to in that way since the 1500s, the time of Rabbi Loew and the Golem. Thus, inspiration for the tagline of Poetry, Thought, Word Magick - motto and promise:

towards Old-New Mastery of the Creative Path

& yet…

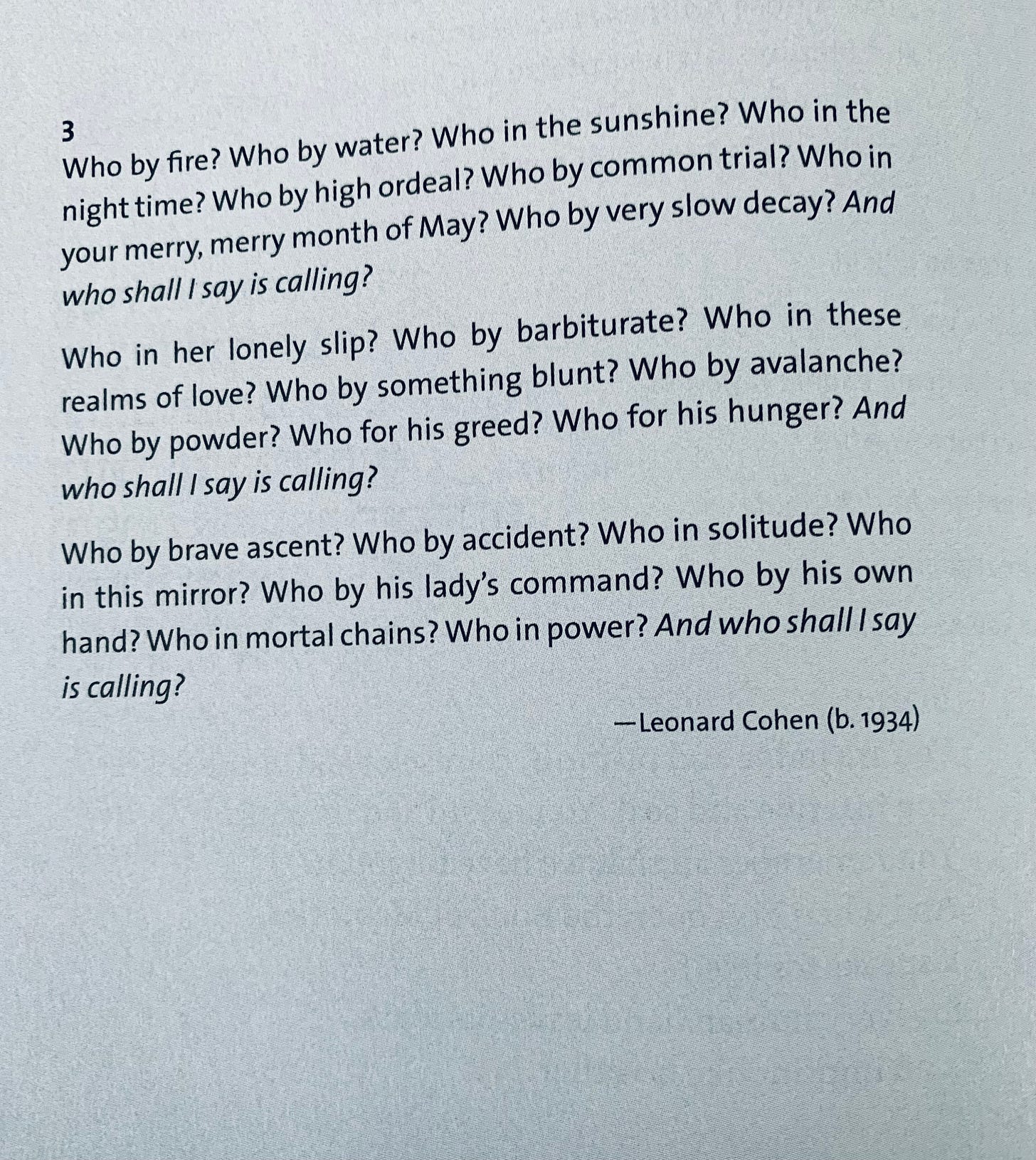

Again, this past Monday, although I made it to services in person this time, I pored through Mishkan Hanefesh - the Yom Kippur volume, brimming with Leonard Cohen.

Who in her lonely slip? Who by barbiturate?

The Yom Kippur volume has even more supplementary poetry, lyrics, and writings than the Rosh Hashanah volume, including Denise Levertov, Yehuda Amichai - both books have more than enough Mary Oliver as to be expected - gratified to see Charles Reznikoff (when I could never find a copy of his undeniable, devastating Holocaust at the bookstore of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in DC) - plus Richard Feynman, Einstein, Gandhi.

Then, beyond the page, in the pews, seeing people I haven’t seen for a long time, someone brought up Jim Carroll’s song “People Who Died,” with reference both to my The Killing Joke forthcoming and - more centrally to Yom Kippur, along with Leonard Cohen’s song as above - to Untaneh Tokef, who by fire, who by water, Carroll’s parallel teenage punk-poetic list of mourning, who by falling from a roof on East Two-nine, who by twenty six reds and a bottle of wine.

Our associate rabbi opened the readings with a Cohen quote, and her caring voice took reverent care of the words. Later, our chief rabbi spoke for the second time - this year and last year - on Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai by Matti Friedman; the quaver in his voice tendered Cohen and his music and the background of his music as a revelation.

Yet, the Hallelujah with traditional lyrics was sung to the tune of Cohen’s strangled, anguished “Hallelujah.” I was less bothered this year, admittedly. Still, with memory of my intense, tense response to the same in 2022 mixing into the experience of 2023, the use of that melody in that way doesn’t sit comfortably in me. It’s an easy thing to overlook. Let’s not. It’s also an easy thing to get over - but let’s not. Let’s dwell. In silence. Let’s take a moment to hear the absence that remains present in Cohen’s music when substituting traditional words for the verses it took him five years and multitudes of drafts to compose.

…

Now after that moment let’s speak the trespass, the appropriation. For a moment. Those “Hallelujah” verses - so personalized, so sexualized, so owned and individuated of fraught desire, of human wrack and imperfection, impurity, how easily were they discarded in their inappropriateness for the universal! For such bright, good communion. This is the age-old complacency of institutionalized religion, such unquestioned prerogative to override the profoundly singular. Similarly, aside from the changing or omission of the actual words of a poet - and here I’m going back to what happened with Ginsberg - if there is a change in the melody of voice itself, of tone, if there’s an imposed conventional religious tonality, that too is a problem. That too is an offense. For tone echoes essence.

To change the tone - or to miss it, or distort it, get it wrong - is to change the voice of the poet. It is an intrusion on par with changing the words.

For nuance of substance reverberates through tone. Accordingly, tone is the key to understanding much literature, to hearing what’s there. If you can get a feel for the author’s tone, suddenly you hear the other’s voice (and this is the meaning of “voice” in literature): then you’re granted access to even the most difficult writing. The key to comprehension of any piece of writing, poetry and prose, limpid or intricate, is hearing the author’s voice, sticking with a text until its tonality is sensed, until the correct tone makes sense of its particular style and phrasings; as a counterpart to “finding one’s voice” for the writer, the reader does well to find the voice in the writing. In so doing - out of time - you find the author talking directly to you, with you, and dead or alive, they are real company. You’re locked in with an everliving interlocutor. (This belies denial or death of the author ideologies, since voice abides, and if you’re not hearing that voice in your mind, you’re not really reading or feeling the way of the text. Like Richard Foreman on meaning,* voice is there to be discovered.)

Another motto inspiration, in keeping with Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater, going back many years now (2005-2010) to Yockadot Poetics Theatre Project:

* “Understand—it always makes sense. Sense can’t be avoided. If it first seems non-sense, wait: roots will reveal themselves.”

Nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah. Today doves let fly off the incision on my tongue.

The poetic act is one thing, the act of prayer another.

liturgical poetry - prayer - vertical language

“The Fast I Desire” Isaiah 58:1-14 the prophet enunciates true religion

Avinu Malkeinu, call and response, Hebrew and English, voiced then sung

Untaneh Tokef, written and sealed

Words and Tones to overcome Babel

The Holy All

yet still not to be confused with - or given rights over, permission to misuse - the still small voice of every individual, what is known through inwardness, meditation, in quiet reading and hearing, in lonely devotion and world-weary tears, and in the heart’s hard-won joys, that individualized voice each is to seek in one’s own standing alone (the essential artistic task, the essential existential task, a sacred attainment in oneness of solitude), within, within the words, standing by one’s words, fulfillment of a personal fate written and sealed, each at One.

Likewise, beware of poetry readings

In the secular context, poetry readings in general have their own detrimental tonality.

I’m thinking of the prevelance of monotonal neutrality; it’s as if, through the use of monotone, the poet can succeed in presenting text without interference by voice, by inflection. As if performance or interpretive reading of one’s own words were “cheating.” As if the words can be served by monotone alone to be heard as words. It could be a matter of taste or coolness, the determination to purge emotion from the voice - reflective of an ethos against sentimental affectation. This for the most part is the norm in staid, standard poetry readings, so-called serious intellectual and academic circles, what’s left of experimental writing and avant-garde coterie. In contrast, Spoken Word has its own gestures and devices of performance that openly engage sentiment - and often do cheat in that way, injecting emotive contrivances into the presentation, empty rhythms, which aren’t effectively upheld by the words themselves, tending towards fads and homogenization of expressive feeling.

Despite this valid fear of playing with emotion/playing to emotion, monotone flattens the text, and really makes poetry readings boring. If not insufferable: purported last words of Joe Brainard of I Remember fame - “At least I don’t have to go to another poetry reading.”

The truth is there is a way of performance that honors the words through performing them - conscious performativity - and seeks to activate that discoverable voice abiding within the text. Such a means lives up to the ethos the use of monotone fails to serve while similarly refusing to cheat with a faked mood, with artifices of imposed external rhythms, stereotypical emotional cadences, whether these be through sacred chanting intonation, Spoken Word devices, or the orotund Shakespearean tone that never gets Shakespeare right, or the grandiose rendering of “elevated” poetry that perhaps only Richard Burton got right. There is a way to let the words themselves drive the style, the pace, the spirals and beats of performance - the words’ own intrinsic provocations in sound and meaning, in flow…

You need to give yourself over to utterance.

As a method, as an artistic path, I’ve been in pursuit of this giving over for decades. I mentioned Yockadot above; for thorough information and credits on that project, scroll down to the bottom of the webpage of A Shared Imagining, an early foray into blogging which traced what came next for me (2011-2016) with poetics theater, poets theater, theater of the word: the book and its accompanying stage work, Idylls for a Bare Stage, which had to develop a specific way towards enacting its text, art of the idyll in practice and theory, a new technique for poetic monologue.

Now, as The Killing Joke awaits publication, once again I’m turning towards theater, in renewed consciousness of tone, the resounding core, ongoing intrinsicality of the word, latest bare necessities and exigencies of these times for the stage. About all of which more soon.