I’m thinking of…

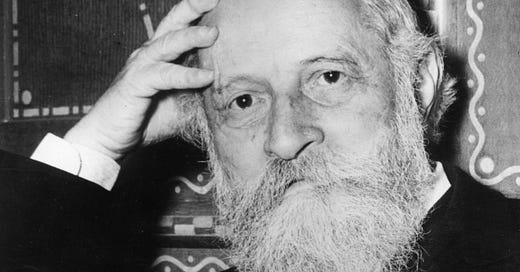

two people who experienced (we learn in autobiographical passages within their works) moments of encounter that bring in their wake lifelong, life-changing commitments - significant Turnings. One is Martin Buber and one is Simon Wiesenthal.

The encounters in themselves are exceptional, almost as if they compelled such profound, fateful responses in each of these men. However, what does it take, what tenacity must a person have residing within, what openness and preparation for the unknown needs to be there for someone to have the capacity to respond so profoundly to an encounter which is, after all, part of a moment like any other moment? There must be something exceptional in such a person - or the readiness for something exceptional.

Martin Buber called his life-historic moment “a conversion.” Within the etymology of that word, there’s turn, further qualified as turn-about - always, for me, the calling is for a turning-towards, internally, what can turn. As here: The Turning

For Buber, already solidly into his philosophic work in his mid-thirties, everything shifted. His responsiveness to a particular encounter - not in the moment but in the aftermath of its moment - was pivotal to his religiosity, conduct of life, and life’s work philosophy: a turning from the soliloquy of mysticism, from monologic prayer and meditation (as times apart, hours removed, such was now forevermore punctured to him as escape and evasion from what is called for in the normal course of a day, in the unfolding of what is just as it is) and a turning towards dialogue, a conversion to conversation in the deepest sense, in its fundamental abyssal depths, his dialogic ethos including but not limited to recognition of the Other outside of convention both in manners and perception, the humane necessity to be truly present with another person, to meet and even to anticipate another human being.

Buber mentions the crucial encounter early in his book Between Man and Man1 (as translated by Ronald Gregor Smith) in a passage with the heading “A Conversion.”

One morning, a young man knocked at his door. It wasn’t unusual for him to have visitors and it wasn’t unusual for him to favor his cogitations over his visitors. He was kindly to the man, but his mind was elsewhere. He didn’t give him proper attention: “I had a visit from an unknown young man without being there in spirit.”

The moment came and went, but it wasn’t until later when Buber became aware of its significance. It was right at the onset of World War I, and that visitor died soon after their encounter; nothing explicit is stated, but there seems to be an air of desperate resignation about his death, equally applicable to his having committed suicide or ending up one of the countless, expendable casualties of war. A mutual friend told Buber that the young man came to him that morning in spiritual need.

Only then did Buber, late, meet the moment not in its time, but in its meaning.

It led to his real work. From then on, he lived in accordance with this understanding of what he had missed by prioritizing religious uplift over what had confronted him in real time, “here where everything happens as it happens.” Now, he would stay in the everyday.

I know no fullness but each mortal hour’s fullness of claim and responsibility.

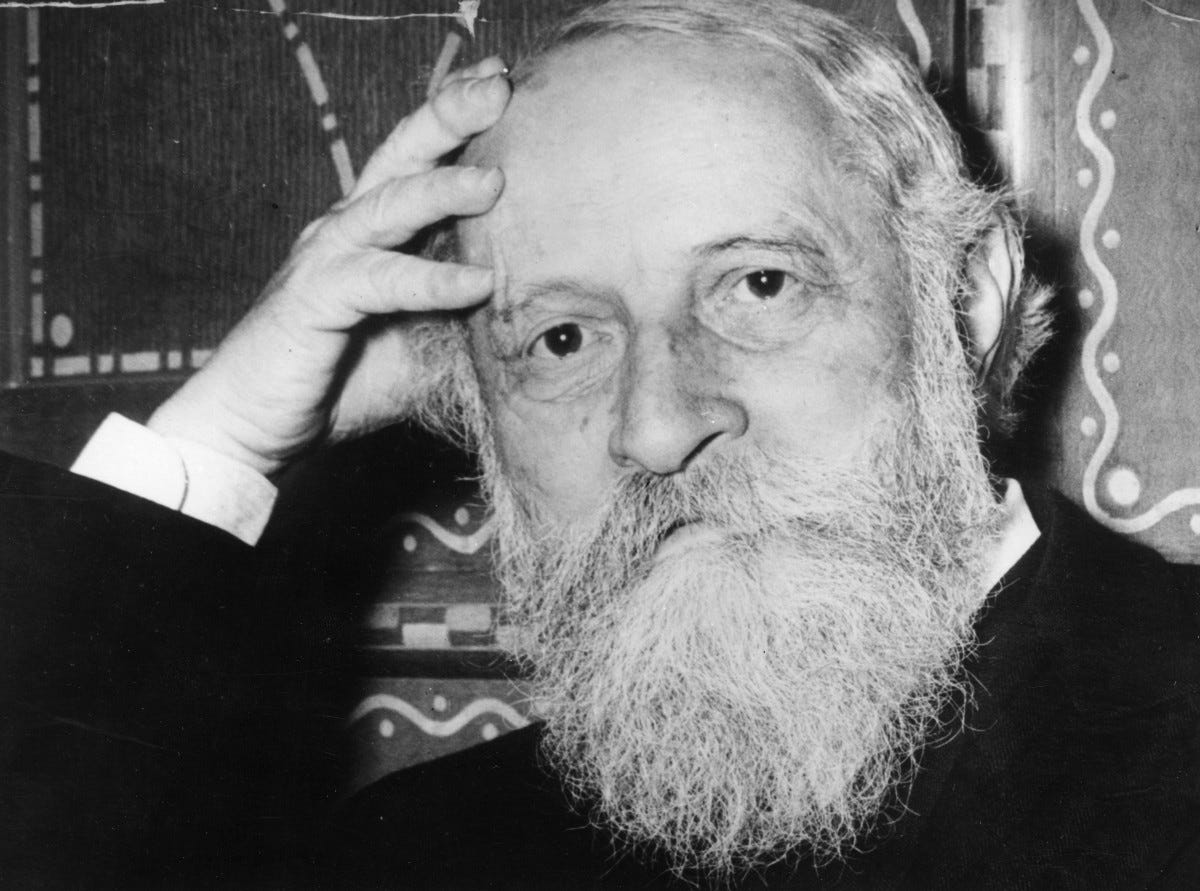

Simon Wiesenthal too experienced an essential encounter.

On the surface, his conclusions and commitments appear to be the flip-side of Buber’s philosophy of facing and interfacing with the subjectivity of another human being in its wholeness. At depth, though, their engagements with the Other are of a piece.

Wiesenthal’s book, The Sunflower: on the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness, centers on this key incident in his life. I alluded to it last spring in my entry on propaganda, early into the war in Ukraine: Sunflowers.

During World War II, Wiesenthal was in the Janowska Concentration Camp in today’s Lviv, Western Ukraine. He was sent with other prisoners on a work detail in the city. A dying Nazi soldier in a makeshift army hospital, his conscience heavy with horrific crimes, calls for the nearest Jew to beg his forgiveness. That person happened to be Simon Wiesenthal.

Wiesenthal spent a lifetime confronting that plea - its implied moral claim on him. He left the man’s bedside without responding directly to him, and then never let go of that moment. The relentlessness of his response to that encounter is extraordinary.

Immediately, in the concentration camp, while engaged in profound self-inquiry amidst atrocity all around, he sought others’ counsel, input, and opinions regarding whether or not he himself were culpable in withholding an answer to the dying man. To forgive or not to forgive? Half the book is a compendium of opinions and, at times, wisdom on the subject a quarter of a century later, and then another quarter of a century again with the latest edition near the turn of the millennium. Although Wiesenthal couldn’t bring himself to forgive, how deep and constant was his inquiry into the request, and how vast his ultimate answer in dedicating the rest of his days to bringing Nazi war criminals to justice wherever they were hiding in the world and however long it took.

There’s no need to doubt the fervency of the young Nazi’s repentance. In context with the situation, though, and in contrast to Wiesenthal’s own persistent responsivity to the inherent humanity of a dying man’s plea, how othered Wiesenthal was! - how used in a manner not in the least reparative or transcendent of the disowned crime! These apex predators - those privileged ones at the top of the food chain who by second nature are predatory, not always consciously so - simply assume everyone else is there to serve them… so any Jew will do for the dying murderous Nazi whose conscience is bothering him (a concentration camp prisoner continuously subject to mortal peril no less); that Jew is waylaid from his forced labor to provide a guilty man the relief he seeks from his suffering.

For Wiesenthal, in his conscientiousness and delving, the issue of forgiveness was a constant consideration. No conventional or platitudinous religious exhortation could be, for him, convincing with regard to what he owed himself or his interlocutor, his enemy; rather, in the commitment he made towards bringing evil to justice, there is a core recognition of the human being behind the monster. The guilty must be held to account.

To bring to justice, to hold to account: such reflects a deepmost practice of intersubjectivity, an utmost respect for the moral responsibility of a human being, and an inmost recognition of another’s - even a Nazi’s - human agency.

For those of us who, for whatever reason, strive to allow the Creative into our ways of being - for art, for life, for survival, for thriving - these two examples of supreme responsivity point to a factor more critical than the development of specific skills or craft: heeding the call.

A crucial moment impinges upon you - of encounter and insight, of experience or inspiration. That moment needn’t fall back into the flow of moments, into the course of things; you can notice its reaching for you and so you can reach back, get a hold of it, pull it out of the stream; then keep hold of it, keep it exceptional, keep it for its meaning and influence on you out of time and, somehow, everpresent. This is what’s transformative. A moment in time, for - given to - a Life-Time.

I’d render the title now as Between Human Beings.